Ukraine: the proposed ceasefire deal

It is almost inconceivable that a war in Europe that could have been avoided if the safeguards put in place in Budapest and Minsk had been followed is heading into it's fourth year. In the meantime people continue to die. However, it's looking like the prospect of a ceasefire has shifted from a pipe dream to a more tangible possibility. The March 2025 Ukraine ceasefire agreement, while still in the early stages of negotiation, has already sparked heated debate among international powers, civil society, and advocates for peace. While the terms of the proposed agreement remain fluid, there are some key points that are emerging.

The March 2025 ceasefire represents a potential turning point in the conflict. It can be argued that the prolonged militarisation of the situation has disproportionately impacted ordinary Ukrainians and Russians, with the economic and social consequences of the war being felt far beyond the battlefield. A ceasefire is seen as an opportunity to pivot away from a war-driven economy to one focused on peace-building, social welfare, and rebuilding civil society. However, significant concerns remain. Critics warn that any agreement must be carefully scrutinised to ensure that it does not legitimise Russian territorial gains or undermine Ukraine's sovereignty. There is also the risk that geopolitical interests, particularly those of NATO, could influence the terms of the ceasefire, pushing Ukraine towards a settlement that may not fully respect the desires of its people for peace and independence. Furthermore, the question of reparations for Ukraine, and the commitment of international powers to prevent further aggression, remains a sticking point.

The Core Terms of the March 2025 Ceasefire Proposal

- Immediate Cessation of Hostilities: The central feature of the ceasefire is the call for an immediate and unconditional halt to military operations. Ukrainian forces and Russian troops would be expected to cease all offensive actions, with both sides agreeing to a suspension of airstrikes, artillery bombardments, and troop movements along the front lines. It would appear that such a ceasefire is necessary not only to save lives but to create space for genuine diplomatic negotiations to take place.

- Creation of Demilitarised Zones and Buffer Areas: In an effort to prevent the conflict from reigniting, the ceasefire agreement includes the establishment of demilitarised zones, particularly in the heavily contested Donbas region and around Crimea. These zones would be monitored by neutral peacekeeping forces, likely under the auspices of the United Nations or the OSCE, to ensure that both sides adhere to the ceasefire terms. This is seen as a crucial measure, allowing for de-escalation while preventing the kind of small-scale skirmishes that could derail the process.

- Humanitarian Access and Civilian Protection: The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine is one of the most pressing concerns of the ceasefire agreement. The proposed deal includes provisions for immediate and unhindered access to humanitarian aid, particularly for civilians trapped in war-torn areas. This would include food, medical supplies, and the restoration of basic services like electricity and water. The ceasefire also demands the protection of civilians in conflict zones, including the establishment of safe corridors for evacuation. It is stressed that the protection of human life must be the foremost priority of any peace deal, not the interests of military elites or international powers.

- Prisoner Exchange and War Crimes Accountability: A significant aspect of the ceasefire is the provision for a mutual exchange of prisoners of war. Both Ukraine and Russia have committed to returning detainees held by either side. More controversially, the agreement includes provisions for a joint international tribunal to address allegations of war crimes committed during the conflict, with Russia being held accountable for its invasion and occupation of Ukrainian territory. This is a particularly sensitive issue, given that any genuine peace agreement must ensure that perpetrators of atrocities are not granted impunity.

- Territorial Disputes and Autonomy for Donbas: One of the most contentious elements of the ceasefire is the status of Crimea and the Donbas region. Ukraine insists on the restoration of its full territorial integrity, while Russia demands recognition of the territories it has annexed. The agreement proposes that these areas be given a special autonomous status under international oversight, but with the clear understanding that any final decision on sovereignty will be subject to a future referendum or negotiated settlement. This remains a deeply polarising issue, with l critics fearing that any compromise on territorial integrity could set a dangerous precedent for global sovereignty norms.

- International Monitoring and Reconstruction Aid: The ceasefire includes provisions for international monitoring of the ceasefire terms, with neutral countries providing oversight to ensure both sides respect the agreement. In parallel, a comprehensive reconstruction plan for Ukraine would be launched, with substantial financial support from international institutions, including the EU, the IMF, and the World Bank. This reconstruction must go beyond physical infrastructure and include the rebuilding of democratic institutions, addressing corruption, and ensuring that Ukraine's future is shaped by its people rather than outside powers.

It would be hoped that the ceasefire could lead to a broader peace process, but there is also a recognition that such a process will require significant concessions from all parties. The challenge, as always, will be ensuring that the voices of the most affected, the people of Ukraine, are heard loud and clear.

Hugh Dellar is an advocate of Ukrainian sovereignty and of peace for the region. As an journalist and English lecturer who has worked with students in a number of Eastern European countries, he is in a unique position to get local opinion on the unfolding events. I have been watching his posts since before the beginning of the war and I saw how he lost many Russians and Belorussian commenters as the war unfolded, who it was clearly obvious from their posts were either (a) following the Kremlin line (b) we washed over with Russian propaganda. I'm sure this was hard for him as he has worked for years with people from these countries and built up a network of students.

Following the announcements last night he did what a lot of us forget to do. He asked the people on the ground what their thoughts were. It's easy to write articles on what is happening and forget the key point that from an office in Teesdale, I don't have to worry about power cuts, food shortages, displacement, taking shelter from attacks and air raids or burying my relatives who've been taken before their time. When, like I am, you're a thousand miles from the frontline with no personal investment in the war, how can we possibly understand the daily horrors?

From the responses he got it has to be said that the optimism was muted to say the least.

These are the human voices on the ground. There is very much a 'we've heard it all before rhetoric around this with a consensus that Russia cannot be trusted.

At the same time, as these discussions are taking place, the war is still taking place also, and it is apparent that the Ukrainians are not prepared to give up their sovereignty on the whip of an untrustworthy ally in the Whitehouse.

At the same time, there seems to be a pushback in Russia for the ceasefire too. Putin may see this as a way out from the quagmire he's dug for Russia and for himself, but there are dissident voices on the far right in Russia who see this as a betrayal.

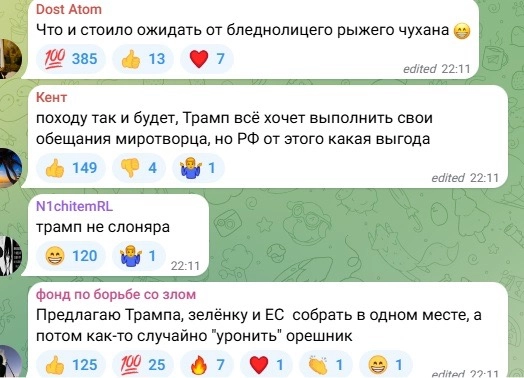

Pro-war portal Operation Z showed this sentiment.

Whil Olga Skabeeva, one of Russia’s leading propagandists, simply asked, “And what do we get in return?”.

This cease fire proposal is far from a done deal. Trump wants his Nobel Peace prize and if he pulls this off he will probably get it. And it's important to realise that a cease fire is not peace. It is the temporary stopping of the war. Putins three day special military operation has gone on for over three years now and the body count on both sides shows what a pointless war this was. Neither Russian or Ukraine can afford to back down so any meaningful peace deal needs to give both sides a victory. That won't be easy to achieve and will be difficult to stomach by the protagonists.

From the point of Eastern Europe, any peace deal needs to set up a scenario where Russia can't make war on Ukraine again, as this would be seen as a stepping stone towards Russia reconquering Moldova, the Baltic States and ultimately a war with Europe, a Europe that is rapidly rearming in response to the new reality.

All wars end at the peace table. The diplomats sat around the table in Jeddah may or may not reach workable political solutions. In the meantime, in Odessa, Kherson, Kyiv and Lviv, the civilians will continue to sleep in their cellars in sleeping bags, de-sentitised to the horror and most likely wondering how the hell we got to here.

The world has gone mad. If you enjoyed reading this, please feel free to look at the rest of the blogs on www.TetleysTLDR.com. They're free to view, there's no paywall, they aren't monetised and I won't ask you to buy me a coffee. Just a leftie, standing in front of another leftie, asking to be read. All the best, Tetley

Example Text