We need to talk about the abolition of NHS England

In an unexpected move, Sir Kier Starmer has today announced the abolition of NHS England, the quango responsible for the strategic leadership, oversight, and delivery of healthcare services across the country. This decision has sparked a wave of uncertainty about the future of the NHS and raised questions about how healthcare will be funded, delivered, and governed moving forward.

On the face of it, NHS England had its problems and few will miss it. NHS England was created in 2013 as part of the Health and Social Care Act 2012, which was driven by the Lib Dems and passed under the Conservative-led coalition government. Prior to this, the NHS had been managed by the Department of Health, but the Health and Social Care Act created NHS England as a separate quango (quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation) with responsibility for overseeing and coordinating the commissioning and delivery of NHS services across England. NHS England replaced the previous structure of strategic health authorities and primary care trusts, and it became the body that was tasked with ensuring the national health service operated efficiently and effectively. Its establishment marked a significant shift in the governance of the NHS, with the aim of making it more streamlined and more focused on outcomes, but it also introduced more market-driven mechanisms into the healthcare system, including greater involvement of the private sector in healthcare commissioning. One of the key reasons it was formed was because the Department of Health could not do the day job of managing the NHS.

NHS England has played a critical role in ensuring that the system operates cohesively across regions, providing leadership on funding, workforce management, and healthcare commissioning. With its abolition, the government has promised a new structure to ensure that healthcare remains universal, equitable, and publicly funded, but the details of what this new structure will look like are still unclear. One of the most pressing questions surrounding this shift is how funding for healthcare services will be managed moving forward. Under the old system, NHS England was instrumental in allocating funding to local NHS trusts and organisations, ensuring that resources were distributed based on population need.

Now, with NHS England abolished, the funding process will become more decentralised, with greater responsibility placed on local authorities and NHS Trusts themselves to manage budgets and service provision. This move towards local control could potentially allow for more tailored, regional approaches to healthcare delivery, with communities having more say in how services are run and funded. However, it also raises concerns about the fragmentation of the system. Without centralised oversight, there is a risk that some regions may struggle to secure adequate funding or face disparities in the quality of care provided.

Additionally, the government's 2024 Procurement Act will play a pivotal role in reshaping the funding structure. The Act is designed to introduce greater private sector involvement in the procurement of healthcare services, allowing private companies to bid for contracts that were previously handled by public organisations. While the Act is sold as a mechanism for improving efficiency and reducing costs, critics argue that it risks opening the door to privatisation, undermining the core principles of the NHS by prioritising profit over patient care.

Local NHS Trusts are at the heart of healthcare delivery, providing vital services across regions. Under NHS England’s stewardship, these Trusts have operated with some degree of autonomy, though ultimately guided by the strategic direction set by NHS England. With the abolition of NHS England, it is unclear how these Trusts will be governed, and whether they will retain the autonomy they need to operate effectively. The Government is marketing this as democratisation of the system, but it’s difficult to see how that is the case.

On the one hand, the move to decentralise decision-making could give local NHS Trusts more freedom to tailor services to the specific needs of their communities. This could be seen as a positive development, allowing for greater innovation and responsiveness at the local level. On the other hand, the increased reliance on local commissioning and procurement may expose Trusts to financial risks and make them more vulnerable to external pressures, especially as private sector companies begin bidding for services traditionally provided by the NHS. The viability of local NHS Trusts could be at risk if they are forced to compete for funding and resources in a more fragmented system. Some Trusts, particularly those in less affluent or rural areas, may struggle to secure the necessary resources to maintain high standards of care. The result could be a postcode lottery of healthcare, with some areas receiving a higher standard of services than others, depending on their ability to attract funding and private sector involvement.

The Procurement Act 2024 was rushed through without any phasing in February 2025 and it is one of the most contentious aspects of the Labour government’s reforms. Already NHS Trusts are feeling the effects of the legislation, and they are not good. The Act introduces a competitive tendering process for the delivery of healthcare services, allowing private companies to bid for contracts previously held by NHS organisations. While the government insists that the Act will improve efficiency and reduce waste, many critics view it as a thinly veiled attempt to privatise key elements of the NHS. The Procurement Act is a deeply concerning development. The move to allow private companies to run public health services and opens the door to corporate influence over healthcare provision. Companies that prioritise profit could be more inclined to reduce costs by cutting corners, potentially compromising patient care. Moreover, this shift could exacerbate existing inequalities, as wealthier areas with more lucrative contracts attract higher quality services, while poorer regions are left with underfunded and overburdened providers. Critics also warn that the Procurement Act could undermine the NHS’s founding principle of universal, free-at-the-point-of-use healthcare. As private companies become more deeply embedded in the system, there is a growing concern that essential services could become subject to charges or rationing, limiting access for those who need it most.

The abolition of NHS England also raises questions about the future of ongoing projects and initiatives aimed at improving public health. Initiatives that focus on reducing waiting times, tackling health inequalities, and addressing the staffing crisis may be left in limbo as the new system is established. With the introduction of more decentralised control and the growing involvement of private providers, there is a risk that these vital projects could be deprioritised or restructured in ways that do not align with public health goals. Moreover, projects designed to improve access to services in underserved communities, or to expand preventative care, could be at risk of being sidelined in favour of more profitable ventures. The increasing involvement of private companies in healthcare procurement raises the question of whether the long-term goals of public health will take a back seat to short-term financial gains. The decision to abolish NHS England and introduce these sweeping reforms is a worrying departure from the party's traditional commitment to maintaining a publicly funded, publicly delivered healthcare system. While decentralisation and local control could theoretically lead to more responsive healthcare, the increased reliance on private sector involvement and competitive tendering poses significant risks. If you remember, hospitals were spotless before CCT (Compulsory Competitive Tendering) was introduced. It’s hard to see how this will be any different.

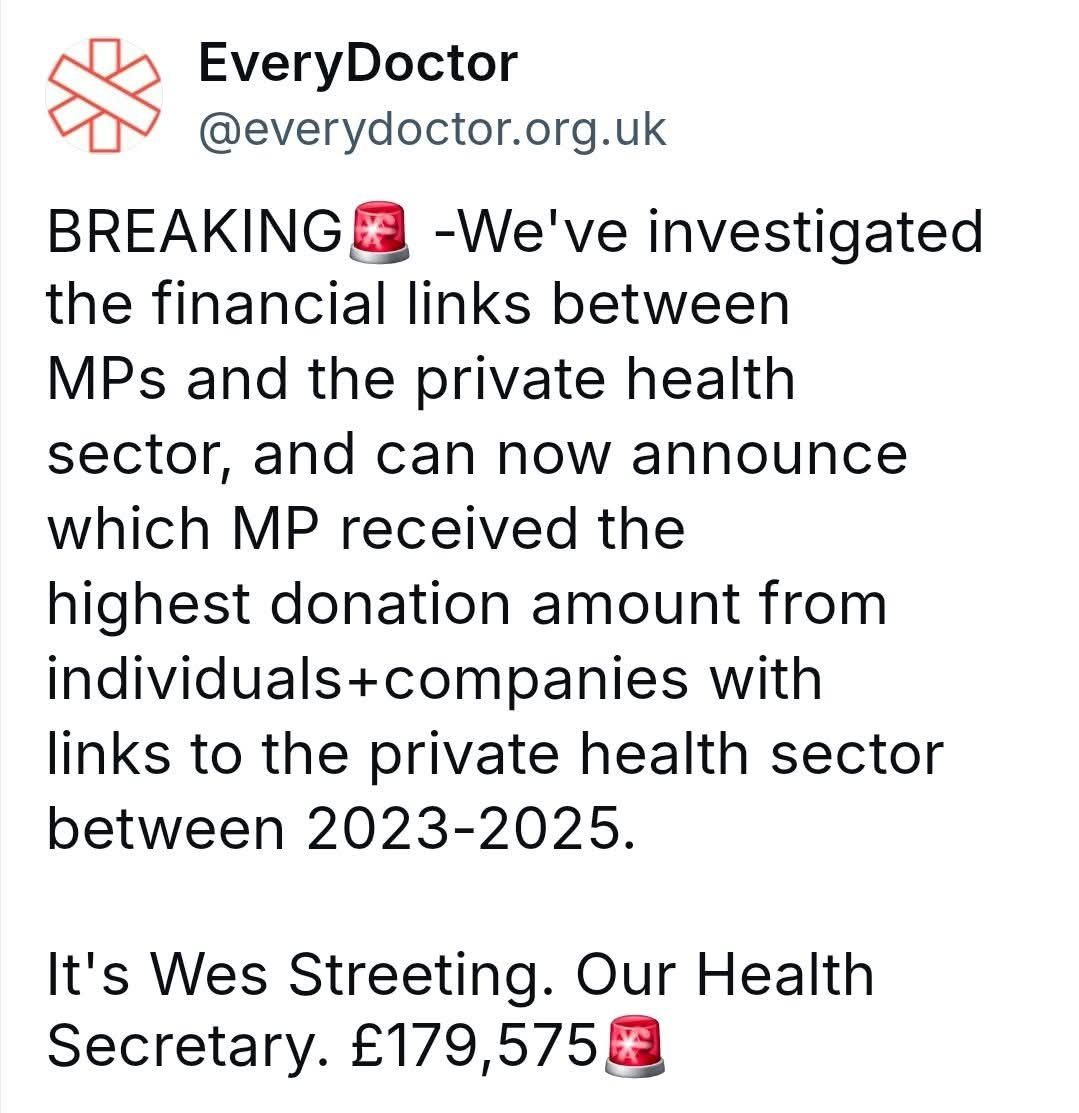

At this point we need to look at the Health Secretary, Wes Streeting as this has him written all over it. Wes Streeting, the current Health Secretary, has faced scrutiny over his financial connections to private healthcare interests. Since entering Parliament in 2015, over 60% of the donations he has received have come from companies and individuals linked to private health, including substantial contributions from MPM Connect and OPD Group Ltd, both controlled by recruitment executive Peter Hearn. Good Law Project Additionally, Streeting accepted a £600 hospitality package from FGS Global, a public relations firm representing major pharmaceutical companies, to attend the Glyndebourne opera in June 2023. privatisation.everydoctor.org.uk While there is no direct evidence linking Streeting to the opaque funding networks associated with 55 Tufton Street, known for housing right-wing think tanks funded by undisclosed donors, LinkedIn his financial ties to private healthcare have raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest and the influence of private entities on public health policy.

It is telling that the far-right populist party Reform UK, and advocate of an insurance based healthcare system, and which is deeply embedded in the same private healthcare pool as Wes Streeting views the abolition of NHS England as an opportunity to advance their vision for NHS reform.

At its core, the NHS has always been about providing healthcare based on need, not profit. If the new system leads to a fragmented, privatised model, it could undermine the very principles upon which the NHS was founded. As the reforms continue to roll out, it will be crucial for campaigners, healthcare workers, and the public to hold the government accountable, ensuring that the NHS remains true to its values of universality, equity, and public service.

The world has gone mad. If you enjoyed reading this, please feel free to look at the rest of the blogs on www.TetleysTLDR.com. They're free to view, there's no paywall, they aren't monetised and I won't ask you to buy me a coffee. Just a leftie, standing in front of another leftie, asking to be read. All the best, Tetley